Things are about to get weird, y’all.

Okay, weirder. And by things, I kinda mean things. Stuff. Things and stuff.

The things and stuff that keep your family fed and clothed (especially clothed). The toilet paper that… well you know what that does for you. Cosmetics and grass seed and rice and that new hose you were gonna get for this year’s garden because you spaced out in October and left your last good hose out over the winter and it cracked just a tiny bit in three places and shot you in the face with murky, foul-smelling hosewater when you tried to rinse the yellow off your car during The Pollening…

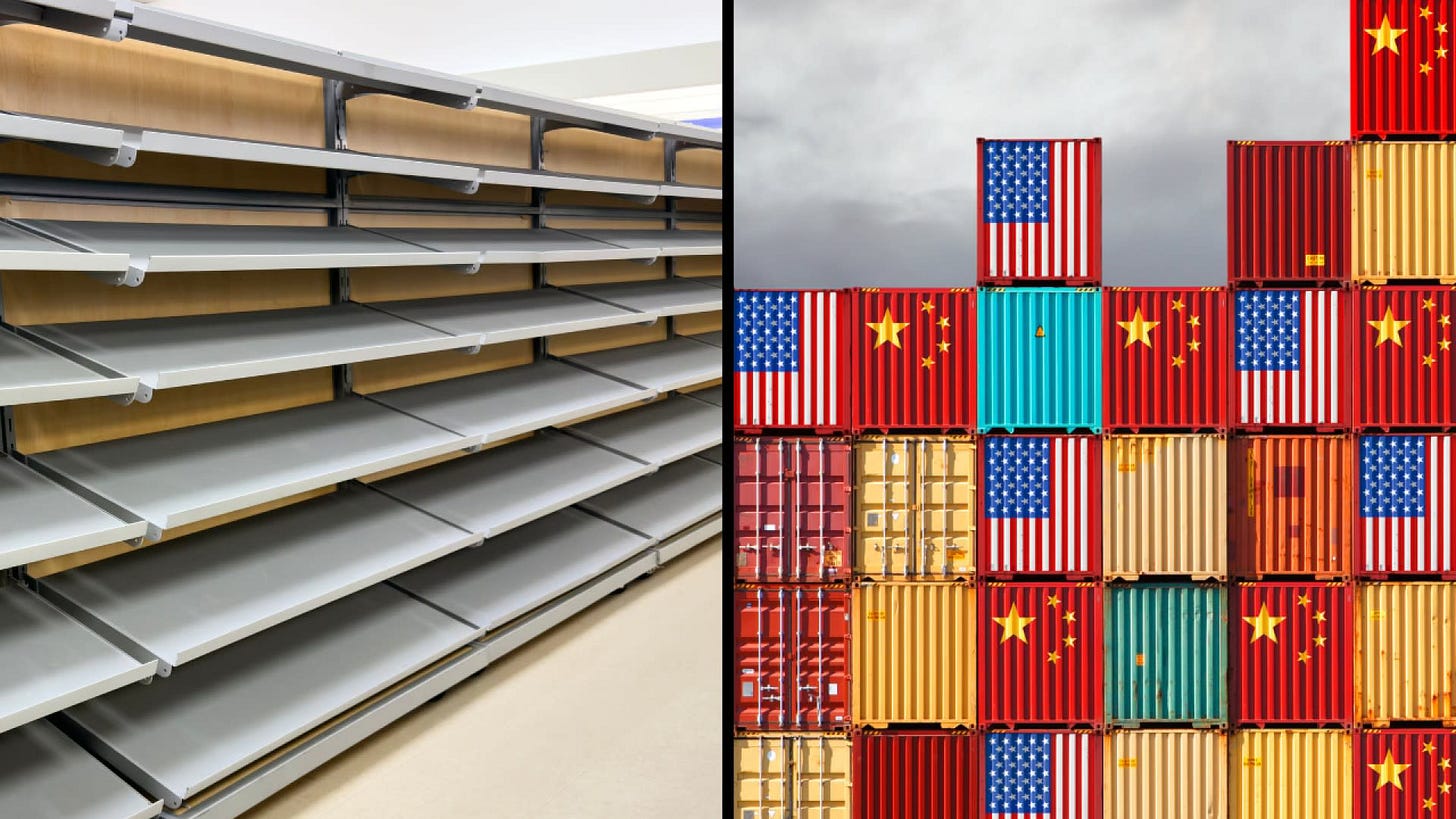

…those things. Some of those things are about to become freakishly expensive. Others simply won’t be on the shelves. It might echo the kinds of shortages we all remember from the early days of COVID.

It might be worse. But it’s definitely going to be weird.

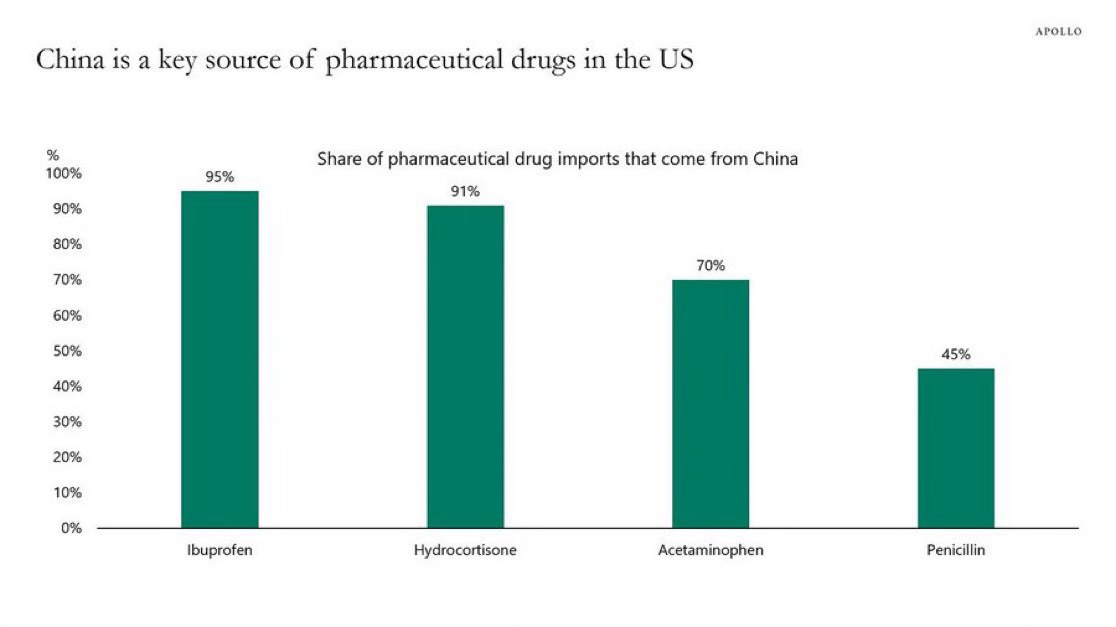

Speaking of pollen, you might want to give not having allergies the ol’ college try. Also, avoid getting poison ivy or bug bites. You’ll save some real money if you just stop having the occasional headache, knee pain, or sinus infection. Lots and lots of the things and stuff that American households turn to for relief of routine ailments, from ibuprofen to anti-itch creams to antibiotics, are gonna be among the many pharmaceutical things and medical stuff which will not be arriving in American ports on big container ships.

In case you missed it — on April 2nd, President Trump used “emergency powers” to circumvent Congress and impose truly absurd import taxes on goods Americans purchase from across the globe (including exports from at least one island populated only by penguins who, it turns out, export a vanishingly small number of goods). A week later, Trump paused those taxes, commonly called tariffs, for 90 days, but left in place a universal 10% tax on all imports and a special 145% tax on goods imported from China. Though hailed in the GOP fever swamps as textbook Art of the Deal-ing from Trump, the pause came on the heels of two big cracks in the financial firmament. The first was a solid week of losses in global equity markets (where stocks are traded, including the NY Stock Exchange), where trillions — with a “t” — of dollars in value evaporated thanks to the Trump plan. Then, just short of a week later, in the late hours of the night, weird things began happening in the bond market. Often called the secondary market, the bond market is where securities are traded. That’s a fancy way of saying debt. The bond market is where US Treasury debt is bought and sold, and that night great hordes of traders and institutions holding US debt started selling it, all at the same time, which is super weird.

Trump said those traders had a case of the “yips”. The “yips” is a sportsball term and refers to unforced errors (dropping the ball, missing the intended target of a throw, etc) caused by unexamined neuroses. This bond sell-off was anything but unforced. Buyers purchase US debt because it has historically been the most stable, secure and predictable place to put money; they sell it when they need cash to cover huge stock market losses and/or when US securities stop feeling feel stable or predictable. Check one-two, the tariffs forced that double whammy.

Before the day was out, a properly terrified Trump administration announced the 90-day pause. Those 90-days will expire in early July. But by then things are already likely to be super weird.

The goods we import from overseas come primarily on big ships. Each ship might carry 20,000 containers or more — quantities so large that, if you tried to send the stuff carried by one boat via air freight instead, it would require 5,000-10,000 flights. Transit times for these big ships can range from 20-60 days or more, depending on origin and destination, so most everything that we receive in US ports must be ordered well in advance. Months.

Since April 2nd, lots of those orders have been put on hold, suspended, and cancelled because the Trump taxes make the goods unsellable; they’re now simply too expensive to unload from the boat. Huge retailers like Wal-Mart and Target and Best Buy expanded their domestic inventories in fear of this trade madness, but in many cases, those reserves are what folks are buying now.

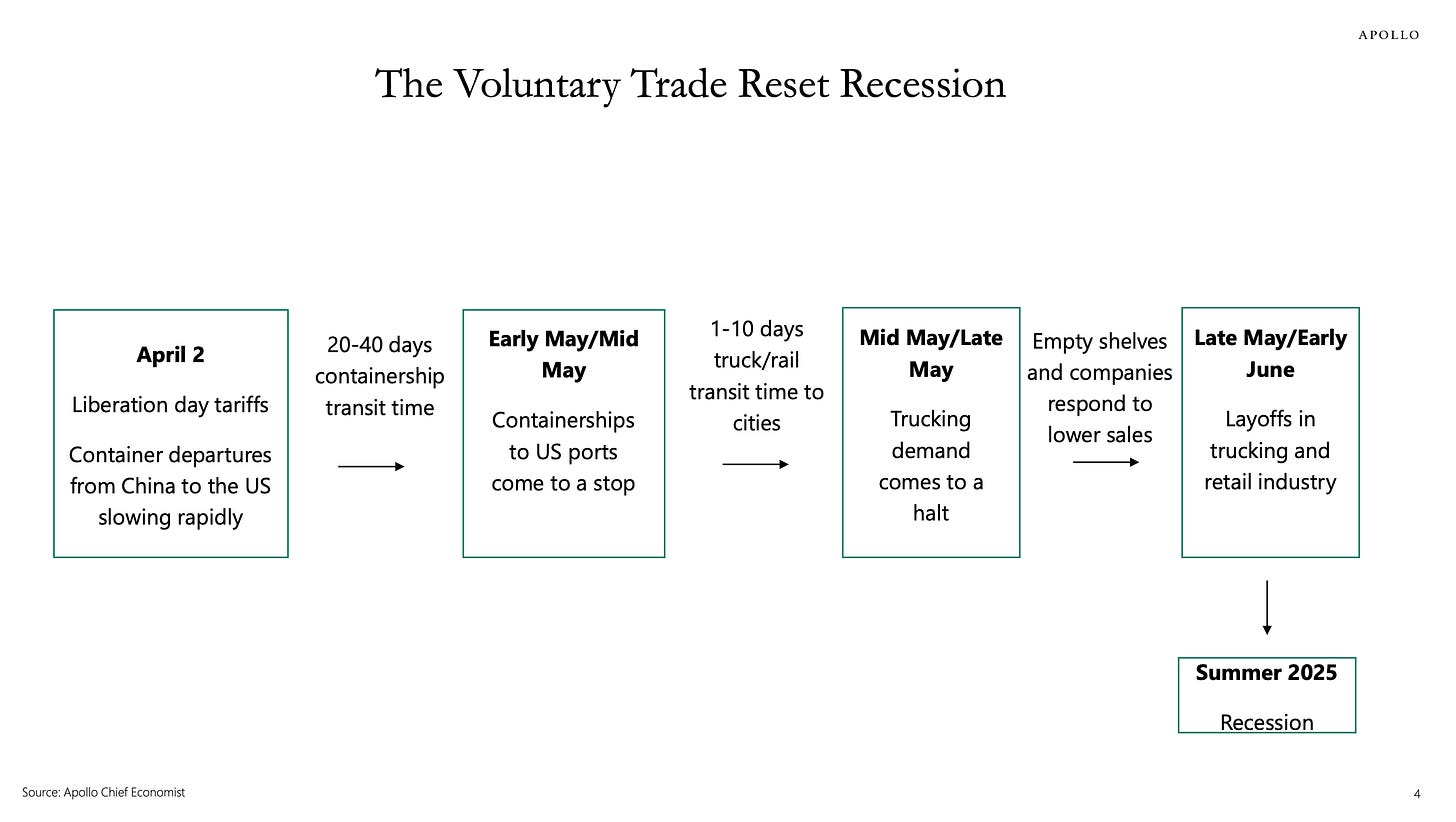

Last Friday, Torsten Slok, the supreme head-honcho economist at Apollo Global Management (a big asset management company in the business of knowing about, y’know, business stuff) warned that we are going to see higher prices — then empty shelves, and layoffs and firings in transportation, with ripples that shoot through the country — all starting within a week or so.

Yeah, a week or so.

The consequence will be empty shelves in US stores in a few weeks and Covid-like shortages for consumers and for firms using Chinese products as intermediate goods.

I recommend having a look at the presentation. It has nice graphs and bullet points about how global tourists are now terrified of traveling to America, and headings which say lovely things like “China to US trade coming to a stop”, and “container freight rates falling”, and “a trade war is a stagflation shock”.

Also there’s this nifty timeline for the extreme weirdness that’s coming.

Things are gonna be weird because a) in addition to his many other failings and deficiencies, Donald Trump, personally, has some hazy notions about trade and foreign policy, along with little demonstrable comprehension of history or macroeconomics, and b) the wider Trump economic team, contains some driven, well-studied, but extraordinarily heterodox figures with something, collectively, like a “concept of a plan” and who are battling each other for enough of the President’s ear to enact a “rebalancing of the international economic system”.

That concept of a plan is also weird…and that weirdness is not exactly like Trump and Vance are weird or like buying fruit roll-ups for your kids is about to get mega-weird. No, this is some avant garde strangeness. The weirdness of the plan can be seen in a now famous paper published last fall by Stephen Miran, the chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, entitled A User's Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System. Within that paper are not only trade policies akin to the Trump tariffs, but other very complex and highly experimental schemes to, for example, greatly (and somewhat permanently) devalue the US dollar, and even radically alter the world’s relationship to the dollar’s current status as a global reserve currency. Miran acknowledges that there are serious risks in messing around with those advanced economic levers. They’re like the settings on your computer that are so potentially devastating that you have to type in your password a few times before you’re allowed to proceed. They could, without question, cause a variety of global financial, political, and foreign policy catastrophes should they fail to be manipulated with surgical precision, composure, patience and a heapin’ helpin’ of cautious, measured diplomacy.

These are NOT characteristics that have ever been ascribed to one Donald J. Trump.

Peter Orzag, former head of the Office of Management and Budget under President Obama and the current CEO of financial consulting firm Lazard, managed to put it quite diplomatically here:

One way of thinking about it is, Stephen Miran, the chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, in November 2024, put out a guide to remaking the world trade system. He identified what the underlying objectives of this set of policies are but then also highlighted that there was a significant risk of adverse market volatility and adverse economic effects, unless it was implemented in a particular way.

And what were the key attributes of implementing in a particular way? It was graduated implementation and forward guidance. Graduated implementation means baby steps — step by step, a little bit at a time. And forward guidance means that you signal way ahead of time what you’re doing in those baby steps to give markets and businesses and consumers plenty of time to adjust.

And I think what we saw over the past week is it was not implemented that way. It was not graduated — it was all at once. And it also took effect in a matter of days, not even months or quarters.

All year, the economist and former Minister of Finance for Greece (briefly), Yanis Varoufakis, has been going around to anyone who will listen, warning of these bigger, far more radical plans, especially the Trump team’s desire to make the US dollar weaker, raising the real cost of buying anything (if your dollar is weak, it buys fewer imports). Of particular note is how, since February, Varoufakis has slightly altered some terms of his argument, dropping all of his language which placed the visionary mantle upon Trump’s particular savvy and genius, in favor of explaining “what his team are up to” and cautioning the world not to “just portray Trump’s people as mere idiots” (emphasis mine). Thankfully, it has become painfully obvious, even to latecomers to reality like Varoufakis, that our President is no wiz at economics, or diplomacy, or basic world geography, or medicine, or law, or weather, or solar eclipses, or… well, it is best to stop listing things now before we spend a week at it.

Yepper. As weird as it may be, our twice-elected President is a deeply stupid and deeply unserious man.

Now, maybe you’re saying, “Milo, you’re the one who sound weirds right now. We get it, you’re a known Cassandra, out here letting uncontrolled TDS make you yank your hair out.” Maybe. (But don’t forget, Cassandra’s prophecies were true, even if the Trojans thought she was as kooky as a cracked garden hose.)

But a supply shock is coming. It’s locked in at this point — because a whole lot of that supply comes on ships. And those ships aren’t sailing.

How long it lasts, how deep it is, not even Cassandra herself could tell you. Some of the ripple effects are predictable, some will surely surprise everyone. Port workers, then truck drivers, will be the first to be curb-stomped by this silliness. Then, well, let’s just say that we’re all very likely to grow extremely tired of the word recession.

After that? Well, I can only promise weird.

What’s it all about? What’s all this economic distress (and you can be sure that, for far too many, that distress will better be named suffering) meant to accomplish?

The common story reported by most media, within the MAGA fever swamps and without, is that the regime’s economic hoopla is an attempt to bring back (“re-shore” if you’re nasty) manufacturing infrastructure to US soil and manufacturing jobs to American workers. Tariffs, or so we have heard several thousand times since Trump got into politics, are meant to discourage the importation of many things US buyers want and convince businesses to make that stuff here. There may or may not be value in a careful, surgical application of such notions — smart people continuously debate trade policy and the supply chain troubles of the pandemic years certainly did make plain just how much the US consumer is accustomed to goods made overseas.

But to those who gleefully gargle the weird, unappetizing, rage-stuffed, populist Ham-Smoothies™ that Trump is blending up, “trade policy” ought to center on re-taking industrial capacity and jobs that were once rightfully ours, but were taken from us — stolen by no-good, funny-talking foreigners through ill-intent and malice — via tactics like government subsidies, by suppressing their own consumer demand, and by various currency manipulations, in addition to generally profiting from a strong US dollar.

During his speech on “Liberation Day” — better known as April 2nd or Wednesday to those who don’t fawn over nincompoops — Trump made it plain, saying,

Foreign leaders have stolen our jobs, foreign cheaters have ransacked our factories, and foreign scavengers have torn aport our once-beautiful American Dream.

And,

For decades, our country has been looted, pillaged, raped and plundered by nations near and far, both friend and foe alike.

Once again, Trump has hyper-fixated upon a quasi-problem — something sort of real and somewhat persistent, much like immigration — and turned it into a nexus of fear and hatred of the other in order to flog a right-populist agenda.

The dream of the Trumpist right-populists hazily recalls a time when, at its peak, around 30% of us worked in that sector instead of the 8% or so that do now. But that dream is, like most things we dream about, a foggy mess of imaginal unrealities jammed together into a barely sensical narrative (and, as we knew in better times, never a sound basis for policy decisions).

For one thing, never mind that it appears that productivity gains derived from automation are responsible for far, far more manufacturing job losses than foreign trade. Oh, and never mind that, alongside automation and trade, it’s recessions that tend to put factory jobs in the rear view mirror permanently (recessions are defined by two continuous quarters of negative economic growth).

If — or more likely, when — the nation falls into a recession, it will destroy not just the imaginary re-shored employment of Trumps’ dreams but America’s real, existing-in-actual-real-reality manufacturing jobs. But what are the odds of that? Funny you should ask. Pundits and analysts and gambling shops and equity firms and, gosh, everyone not strangely beholden to a vulgar and vapid rage-monster, reckons the likelihood of a tariff-driven recession is now somewhere between a coin-flip and 90% for the US this year.

The odds on a recession are likely to go up after today’s announcement that we are officially half-way there. In the first quarter of this year, all but 20 days of which were under Trump’s watch, the US economy fell from the previous quarter’s +2.4% growth to -0.3%. Most analysts say it’s due to all that stocking up by companies who front-loaded orders in order to have some reserve inventory when the Trump taxes began and the ships stopped sailing.

So, if/when the recession arrives, it will be wholly unnecessary and wholly due to Trump’s populist reveries.

In these reveries, very manly Americans get up in the morning, kiss the wife and kids, head off to extremely manly work, done with manly hands, and… well, you know the rest. It’s pretty gross and definitely creepy, but it’s part of the American mythology, one of the countless stories we make up about ourselves and our history. And that’s fine. Mostly. Kinda.

It’s fine as long as we understand its function as a story, as one of our tales told around campfires. It’s a dangerous thing to forget. On one hand, wildly monstrous stuff has been known to happen when you slip up and let those cultural mythologies start to become cultural aspirations: you end up hiring Leni Riefenstahl to get those aspirations on film. On another hand, confusing our made-up stories of America’s past with our goals for the future puts you in danger of doing other dumb stuff, like accidentally re-inventing feudal serfdom. Whoopsy-daisies! That’s what seemed to happen to Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick while being interviewed by CNBC on Tuesday.

It's time to train people not to do the jobs of the past, but to do the great jobs of the future. This is the new model where you work in these kinds of plants for the rest of your life and your kids work here and your grandkids work here. We let the auto plants go overseas.

A cynical person might wonder if those are the jobs he wants for his kids.

(As it happens, they really, really aren’t. Lutnick chose the path of pure nepotism and handed his multi-million dollar consulting firm over to his 27 & 28 year old sons, who maybe, probably, definitely earned the positions solely on merit.)

What a sensible and generous person might think about these comments is this: what Lutnick is trying to sell isn’t an auto-worker’s job at all. Nor is he mythologizing a coal-miner’s job (don’t get me started), a steel-mill job, a factory job, or really anything that has anything to do with manly, American manufacturing.

What Lutnick is selling is a union job.

Those were the jobs that generations of Americans — the parents, kids and grandkids that Lutnick imagines — sought out in Detroit or across the rust-belt during the heyday of manufacturing. Those jobs featured union-negotiated insurance, pensions, and salaries that could support families and pay for some kids to leave for college full-up with prayers that they wouldn’t have to do the back-breaking factory labor that their parents and grandparents did.

(As an aside, one would certainly hate to think there’s some darker motivations for steering the American economy away from the Biden admin’s rather incredible recovery and especially its achievement of full-employment. I imagine that a fully employed workforce is, oooh, let’s say disconcerting, to some chunk of the employer class. When no-one’s looking for a job, the employees start to get uppity about selling themselves, their children, and their grandchildren to their corporate overlords. At the very least they’re likely to have some ideas about what they’d like in return.)

The chances that these Trump tariffs bring back a golden age of American manufacturing lie somewhere between highly improbable and there’s no way in hell. And there’s a hundred reasons why that’s true, reasons we’ll all surely gain greater knowledge of and appreciation for in the coming weeks and months.

But maybe the main reason is — inescapably — this…

…if you truly wanted to bring US manufacturing jobs to the US, the jobs you believe are now in Mexico, Vietnam, and China, and you drove the US into a recession (or depression) stopping imports to accomplish it, there’s a whole container ship full of things you’d be doing behind your ham-fisted wall of import taxes.

You’d be throwing enormous American federal resources — hundreds and hundreds of billions of dollars — into all kinds of infrastructure, and tossing every golden egg you could find at subsidizing industrial construction and building out supply chains.

Instead of cutting funds to universities and the NSF and letting DOGE cannibalize a thousand vectors of America’s long-established intellectual and scientific dominance because you’re terrified that black lesbians might get jobs, you’d be doubling or tripling or quintupling the number of federal dollars that feed the engines of innovation upon which American manufacturing just might mount a resurgence against China.

You’d set aside the conspiracy-addled dipshittery undergirding climate denialism and fully embrace a clean-energy revolution. You’d immediately stop disincentivizing the manufacture of electric vehicles. You’d act like an adult and shut the hell up about coal, lose the infantile “drill, baby, drill”, and instead get to work building a 21st century nationwide electric grid capable of safely, responsibly and cheaply powering your radical resurgence of modern manufacturing facilities. Yes, Donald, that means windmills. Lots and lots of big, beautiful windmills.

You’d never, ever pass trillions in further tax cuts for the wealthy elite. You’re gonna need that money and more. So you, if you wanted to pay for making your China-busting dreams into realities, would fully fund the IRS to squeeze every last dollar from wealthy tax cheats. You have stuff to pay for here, Mr Manufacturing! And no matter how much you sprinkle pixie-dust and believe, taxing the American consumer through tariffs will not be be paying for it.

That’s Not. How. Things. Work. You. Big. Dummy.

In the big picture, you’d embrace this reality, realize it’s 2025, and quit looking to Presidents Jackson or McKinley or the 1930s and the 1950s for your inspiration. How do you think China became a powerhouse of production? I can assure you it required zero amounts of gazing with weird affection at some freakish dream of their past. Because that’s seriously weird.

That’s the bottom line. Full stop. If Donald Trump truly desired to Make American Industry Great Again, it would look nothing like what Donald Trump is doing to America.

Because what he’s doing is nothing more than putting the world’s strongest economy in our rear-view mirror.

I’m Milo Baynes. Thanks for trusting me with your time.

@milobaynes.bsky.social

Prolly my favorite thus far!

Another phenomenally written piece. I nearly had a spot take when I read dipshittery. Sorry it took me so long to read it. I was on a mental health break from news.